From 1977 to 2017 – 40 years of conservation

dal

1977

al

2017

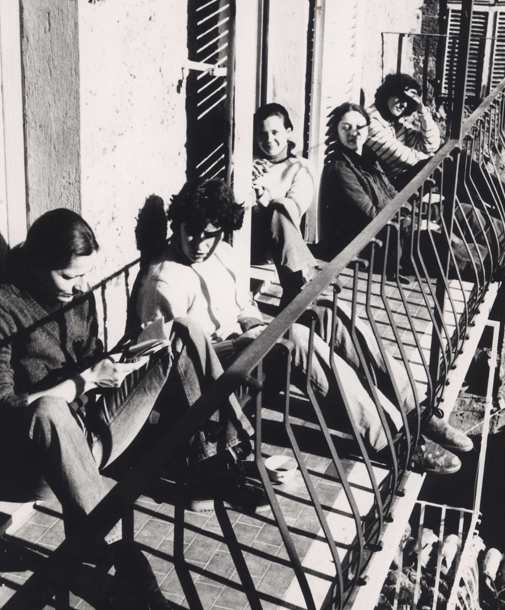

We were full of ideas and enthusiasm – and not a little trepidation – but felt we held in the future in the palms of our hands – very different from present uncertain times. We were lucky too, not the least in having the luminaries who had been our teachers: Giovanni Urbani, Paolo and Laura Mora, Alma Maria Tantillo, Mara Nimmo, Marisa Laurenzi Tabasso Maurizio Marabelli as well as Michele Cordaro, Rosalia Varoli Piazza and Giuseppe Basile.

The training worksite for all four years of the course had been no less than the Basilica of St Francis at Assisi where we had worked on Simone Martini and Giotto.

We had deliberately included Conservazione rather than the more common Restauro as part of our name to underline the more considered and less invasive connotations of the former compared to the latter. Mind you, later, in a moment of despondency over the rather lackadaisical guidelines being handed out by the Ministry of Culture, we played with the idea of changing our moniker to ROAR Restauro Opere d’ARte (Art Works Restored/Redone), which seemed more in tune with the times and a bit more aggressive in flavour. Over these forty years some have continued on the same journey, some have left to take other paths while others have stepped in to join us; indeed, many of our colleagues in the wider world started their careers walking a while with us.

Basilica of San Francesco, Assisi

As students at the training worksite at the Basilica at Assisi, we were clearing up in preparation for a site visit by the Director of the ICR,Giovanni Urbani, when we found a hermetically sealed glass jar containing a by-now supersaturated concentration of Paraloid B72 resin stuck immovably to a plank.

Two students, including a future member of the Co-operative, were given the task of removing this highly unprofessional object. Filled with verve, they set to injecting large quantities of solvent between the glass jar and wooden plank to dissolve the bond. After much fruitless toil they exchanged a look and, without a further word, turned the plank over, leaving the jar stuck upside down on the underside of the scaffolding.

From this episode they drew several useful lessons concerning the futility of much human endeavor, the alleged reversibility of conservation materials and, not least, how being a conservator means finding a solution, no matter what.

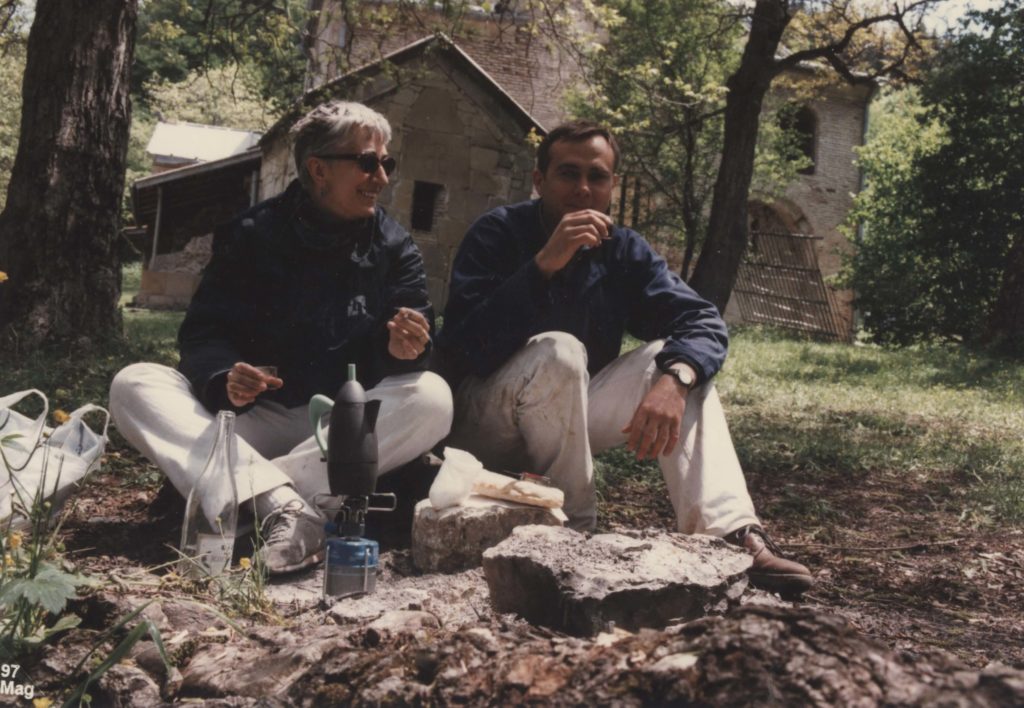

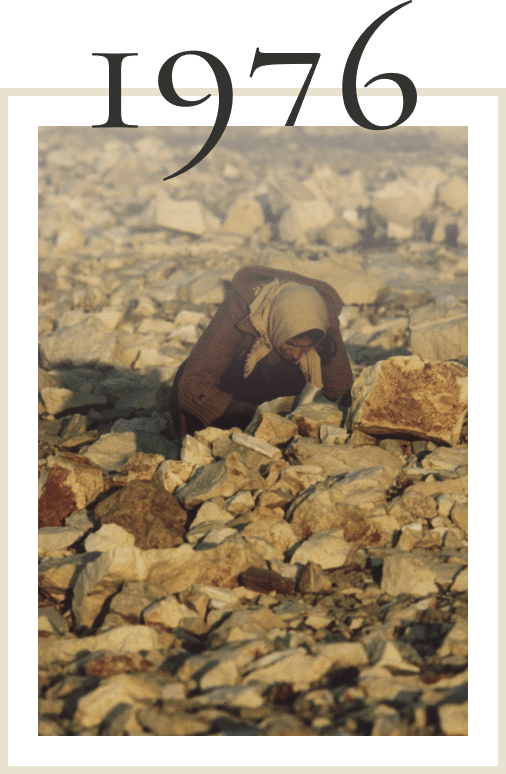

Friuli, at work after the earthquake

Two of the future founders of the Co-operative found themselves carrying out emergency treatments near Pordenone after the disastrous earthquake of 1976. This involved facing what seemed most of the mural paintings of Friuli with muslin and B-72 resin, in preparation for detachment using the method of “face, brace and rip” perfected by the conservator Peppe Moro.

One day, they visited the oasis of calm of the worksite at Villuzza, under the direction of Mara Nimmo, and there they had an epiphany concerning the hitherto unresolved dualism between the active and the contemplative in conservation.

Muslin facing cloth from Pordenone and from Villuzza, while apparently identical, represent these two opposite facets of conservation, both vital to our professional development: they teach us that while at times one can act without needing to think, at others it often may be better to think rather than to act. And so, from the start we have been trying to keep these contraries in balance.

Palazzo Comunale at Pistoia

Some future members of CBC, while working with friends at Pistoia, left a jar of matt varnish on the windowsill of Palazzo Comunale, so that its congealed wax component would dissolve in the sunlight.

But the flag of the Comune, flapping in the wind, flicked up and dislodged the jar so it broke against the great sandstone coat of arms of the Palazzo. The contents not only consolidated the balls of the Medici, but also varnished the car of one Signor Gori, council worker.

Armed with cans of solvents and wads of cotton wool, two of the group ran downstairs and with great professionalism de-varnished the Fiat 500. True, the car’s paintwork was somewhat less shiny by the end of treatment, and there were a few annoying wisps of cotton stuck to its body, but Sig. Gori drove away content for the greater glory of the Museum, and the future CBC members had once again been tempered for future crises.

Mindful of our training at the Istituto, CBC right from the start took particular care over the problems of documentation. With earnest enthusiasm, we photographed and immortalised every micro crack of each work, filling the Ministry’s archives with fascinating though not always entertaining material.

In the archives of the CBC there are some photos which are highly prized due to an important property they share: it is impossible to tell what was being photographed. Consequently, they can be re-used in almost any context.

More frequently, however, we use graphic documentation, which is, according to the best sources, much more objective and scientific than photographs.

Amongst our many graphic maps, we show here one of the more significant examples, expressly requested by our clients (who as we know, are always right) to be in 1:1 scale. The rough copy was diligently traced on-site at Assisi and then re-worked (with some difficulty) to a fair copy in our lodgings near the Petrignano pig farm. The map was particularly noteworthy for its ease of use and ergonomic handling.

1987 (Above and below)

Talking of ergonomic handling. Orvieto Cathedral. 1:1 map of the bay of Christ the Judge

1987 (Above and below)

Talking of ergonomic handling. Orvieto Cathedral. 1:1 map of the bay of Christ the Judge

2017

A different ball game with laser scanner …. Venice, Church of San Sebastiano. 3D map

2017

A different ball game with laser scanner …. Venice, Church of San Sebastiano. 3D map

1978

Maximum detail in a map: Assisi, Basilica of St Francis. Detail of a loss retouched in water color (scale 1:1)

1978

Maximum detail in a map: Assisi, Basilica of St Francis. Detail of a loss retouched in water color (scale 1:1)

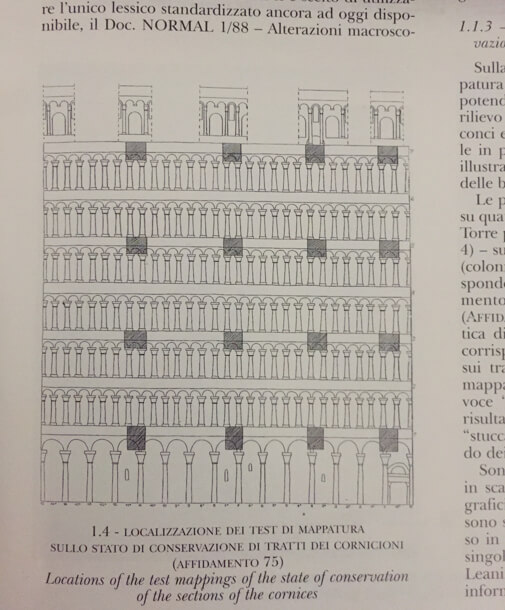

1996

Maximum concision in a map: The whole of the Tower of Pisa on (less than) one page (scale 1:3000 approx.)

1996

Maximum concision in a map: The whole of the Tower of Pisa on (less than) one page (scale 1:3000 approx.)

2003

Matera, Crypt of the Original Sin

2003

Matera, Crypt of the Original Sin

2010

Milan, Room of the Caryatids

2010

Milan, Room of the Caryatids

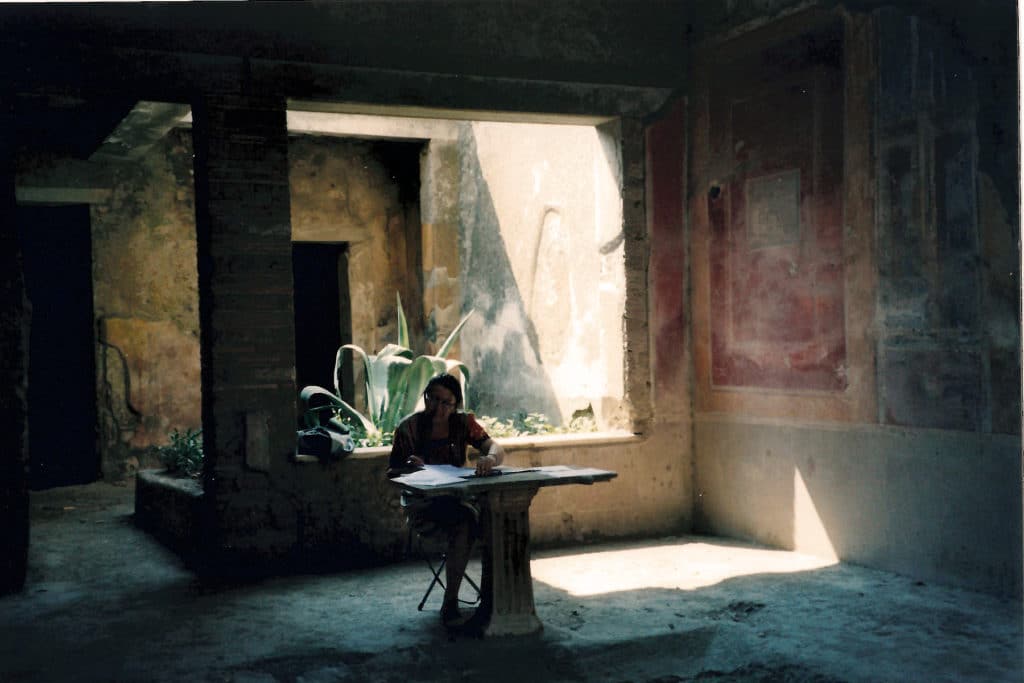

2004

Pompei, Archaeological site

2004

Pompei, Archaeological site

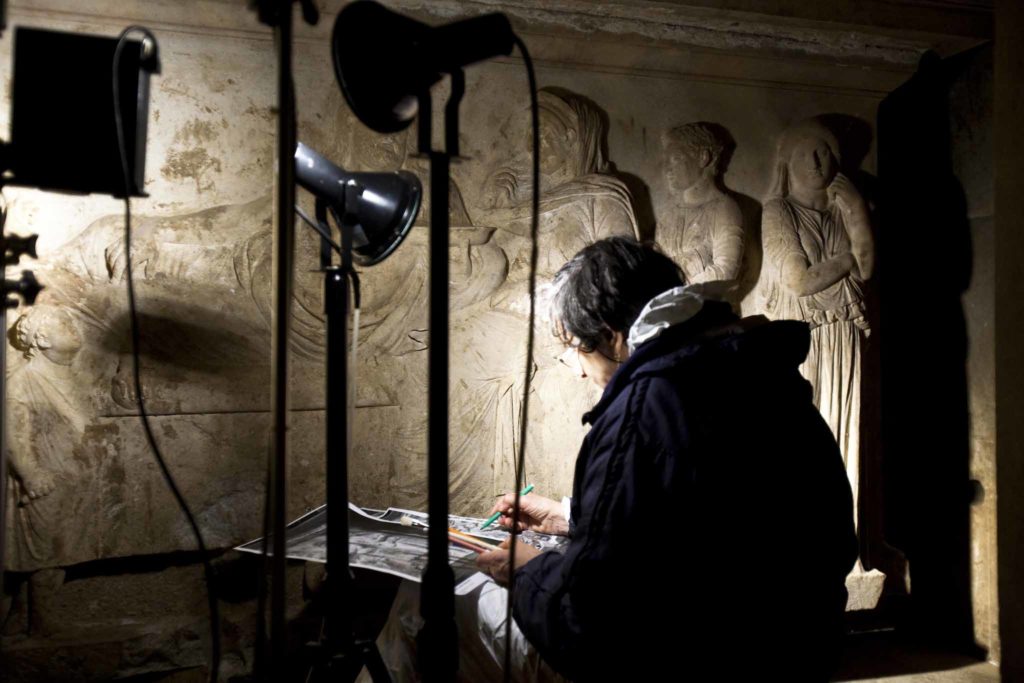

2015

Turkey, Mylas

2015

Turkey, Mylas

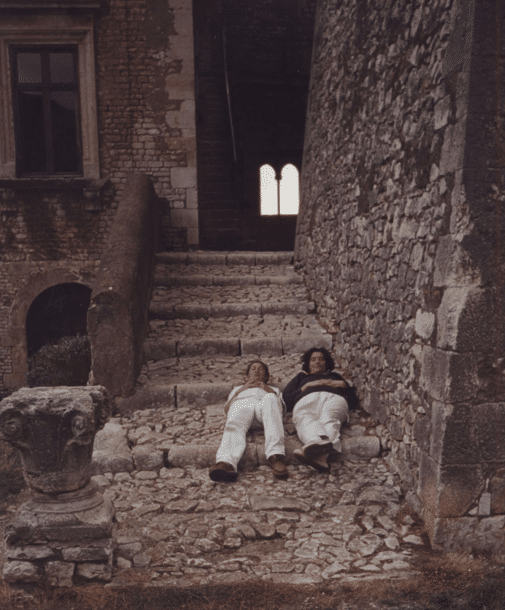

1978

Rieti

1978

Rieti

2016

Auschwitz

2016

Auschwitz

1984

Orvieto, Madonna del Maitani

1984

Orvieto, Madonna del Maitani

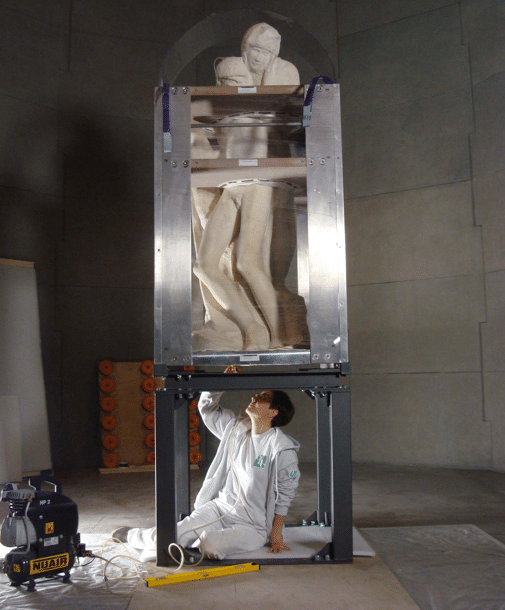

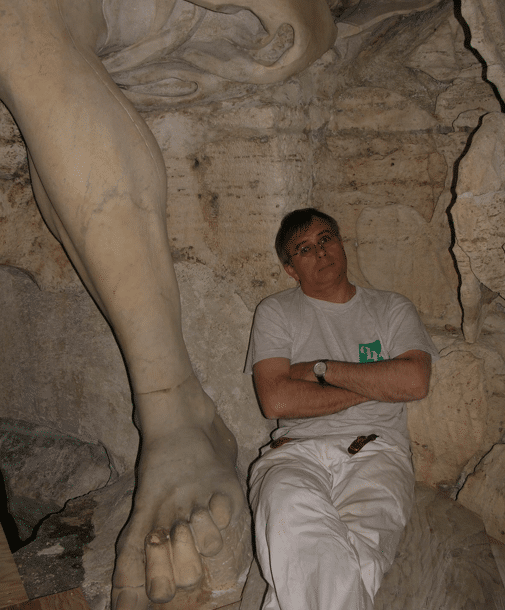

2015

Milano, Pietà Rondanini

2015

Milano, Pietà Rondanini

The conservator has to be many things at the same time: a highly specialised technician, an expert in many branches of human knowledge, even an artisan – though they never seem to have tools to call their own.

Whoever thinks that being a conservator means working in comfort and safety has never passed any time in CBC: we have operated under driving snow and torrential rain, under baking sun or in relentless wind sustained only by much dry humour, achieving great results with whatever tools we had to hand.